- Home

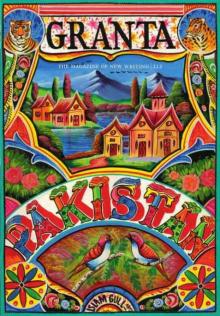

- Freeman, John

B005OWFTDW EBOK Page 5

B005OWFTDW EBOK Read online

Page 5

‘It’s a miracle,’ a servant girl said.

Razia lost her temper. ‘A miracle? The mosque appearing on the river island was a miracle. This is an illusion, some example of the arts of the black realms.’

‘Yes,’ the bodyguard nodded, thinking. ‘It must be some trick.’

Razia muttered to herself, ‘A miracle! Why would Allah waste His attentions on a wife who allows her body to continue disobeying her husband and in-laws? On a Muslim who rejects the company of men as supremely spiritual as these nine?’

She sent for their sharpest scissors but all they could find was a large rusty pair the shrine-keepers used on thorn bushes. With them she tried to cut back the flight feathers a few at a time. They proved to be composed of too resistant a material, and it was noon by the time she managed to reduce each wing to just the bony outer ridge, the ceiling of the room covered with down and the segmented feathers – they had all floated upwards on becoming free. ‘There is an explanation for everything,’ Razia said as she watched them rising all around her. ‘It must be due to the static electricity.’

To prove that the wings were indeed an illusion, and weren’t connected in any meaningful way with Leila’s body, she summoned the butcher.

With an array of knives and cleavers beside him, the butcher positioned Leila on her side on the courtyard floor, held the tattered remains of the wings firmly in place by squatting on them, and made the first quick incision close to the shoulder blades. Leila didn’t feel anything, and for Razia it was a vindication. She reached out her finger and touched the wound and it was then that a trickle of blood appeared and Leila cried out in pain. She struggled to sit up, her violent movements causing the cut to become elongated and tear. They overpowered her, and with the pain making her scream to Allah and all of His 124,000 prophets for help, the butcher detached them with several swings of the cleaver. There was so much blood from the two appendages that it looked like a small massacre, and everyone and everything close by was freckled with red. Barely conscious, Leila sobbed and attempted to crawl away. But she was like a maimed animal. The servant girls struggled to hold her down again as the wounds were stitched up with shoemakers’ twine.

A journalist who happened to be present at the crumbling seventeenth-century shrine, to write an article lamenting the decrepit condition of Pakistan’s historical buildings and monuments, witnessed the entire procedure and immediately sat down on the veranda to write the story of the wings. Razia had noticed him earlier, looking horrified as he watched. Now she stopped on the veranda for a moment on her way indoors and said, ‘There was no need for you to be so upset, son. But then you men don’t understand anything about women’s bodies – we can take more pain than you.’

Inside, she said to Leila, ‘I hope you won’t take too long to heal.’ She was dusting the wounds with the ash of a reed prayer mat she had had burned for the purpose. ‘When we get home you will be ready to receive Timur again. The new wife is going to give him a son very soon, and yours too is bound to be a boy next time. It’ll be your fifth pregnancy and five is a fundamental number of our glorious religion. There are five prayers in the day, and Islam has five pillars.’ She gained eloquence as she talked. ‘Taste, smell, sight, touch and hearing. Allah in His wisdom gave us five external senses, and five internal – common sense, estimation, recollection, reflection and imagination.’

She spoke to the nine exalted personages to see if they would honour Leila with the favour of their continued presence. They not only refused, but also asked them to leave immediately. The men appeared afraid of the shrine itself now, looking stricken at the merest noise – three of them wondering if the she-djinns of the legend had returned to the building, two of them fleeing even before Razia and Leila had left.

Passing through a city on the return journey, Razia had the driver stop at a hospital so a doctor could examine Leila’s wounds. A commotion broke out while they were there. A woman who had just given birth began shouting that her newborn male had been exchanged with a female, refusing to accept that she had produced a girl, labelling the hospital staff liars and criminals and sinners, and calling down Allah’s fury on them. When the exasperated doctors said that if she did not relent they would carry out a DNA test immediately, she stopped protesting and agreed that, yes, the girl baby was hers. Her postman husband had warned her that she would be thrown out on to the streets if she brought home a seventh daughter.

‘I have heard that nurses and doctors at hospitals can be bribed to exchange female newborns with male ones,’ a woman whispered to Razia, and Razia shuddered, grateful that Allah had given her the foresight to keep her own daughters-in-law at home.

The black jeep arrived back at the mansion at dawn. Everything was silent. In the men’s section the party in anticipation of Timur’s son had ended some hours ago, a few revellers asleep among the rose bushes. Leila’s grey-glass eyes had remained closed throughout the journey, with a weak sigh escaping her lips now and then, and she was carried up to the bedroom. Razia stood by the bed hesitatingly for a few moments, but then went out to get the hammer and nails.

Leila opened her eyes and sat up carefully, shivering and trying not to weep. She looked at the picture hanging directly above the bed – a man and a woman in a flowering grove, a peacock on a bough near them, the tail exquisite, the feet dry and gnarled. She had concealed a knife behind it the previous week, considering it the easiest place to reach during Timur’s upcoming night visits to her.

From her waistband she took the music box she had come across at the hospital – an orderly said he had found it on the stump of a jacaranda tree some years ago and that she could have it. Sitting there with her raw shredded shoulders, she began to turn the crank.

Hundreds of miles away in the city of Lahore, he placed the glass of water on the aluminium table in front of him and became very still. He had just finished work and was having a meal on the street named after the slave girl Anarkali, whom Emperor Akbar had had walled up alive for having an affair with the Crown prince. He worked as a driver for a printing press, delivering bundles of newspapers to various corners of the city before the sun rose. He had very few long-term memories and at times he was doubtful even of the most basic facts about himself. Had that happened? Who was she and where is she now? Who was he? During the previous months there had been hours that had come at him like spears, at different angles – sometimes it was his body that was in pain, at others his mind. Everyone believed him to be mute, a few even mad.

He got up and walked towards the motorbike, the sky glistening with light above him. Mynahs and crows that had been sitting without trepidation in the middle of the empty roads lifted themselves into the air briefly to let him pass. At the train station there was an unbroken beeping from the metal detectors that had been installed since the jihadi attacks began, but they were unmanned and everyone and everything was getting through, setting them off. He bought a ticket, indicating the destination by pointing to the chart on the wall. It was almost involuntary: it felt like falling, or like rising in a dream. The motorbike had to travel in the goods carriage and when they asked him for his name, to be put on the receipt, he spoke for the first time since the day he’d buried his brother.

‘My name is Leila.’

The train began its journey and he sat looking out of the window, the dead memory stirring as he went through the land he knew, past the basement snooker clubs full of teenagers, past the mosque whose mullah had decreed polio vaccination a Western conspiracy but had then made announcements in its favour after his own little daughter was taken by the disease, past the house of a dying man whose five children could not come to his deathbed because they had sought asylum in Western countries, past the policeman who stopped by the roadside to take a deep drag from a hashish smoker’s cigarette, past cart donkeys no bigger than goats who were pulling monumental loads along thoroughfares where humans were being beaten and abused in prisons, madhouses, schools and orphanages, past the words on th

e back of a rickshaw that playfully warned the driver behind it: Don’t come too near or love will result, past the dark-skinned woman who had used so much skin-bleaching cream that although she was now pale, she bruised at the merest of touches, past the college boy reading a novel in which the only detailed descriptions occurred during sex and torture or during sexual torture, past the beggars whose bodies had been devoured by hunger, past the green ponds above which insects the size of tin-openers were flying, past the towns and cities and villages of his immense homeland of heartbreaking beauty, containing saints and sinners and a gentle religion, kind mothers and dutiful fathers who indulged their obedient children, its crimson dawns and its blue-smoke dusks, and its unforgivable cruelty, its jasmine flowers that lived as briefly as bursts of laughter and its minarets from where Allah was pleaded with to send the monsoon rains, and from where Allah was pleaded with to end the monsoon rains, and its unforgivable dishonesty, its rich for whom the poor died shallower deaths, its poor to whom only stories about hunger seemed true, its snow-blind mountains and sunburned deserts and beehives producing honey as sweet as the sound of Urdu, and its unforgivable brutality, and its unforgivable dishonesty, and its unforgivable cruelty, past the boy sending a text message to the girl he loved, past the two shopkeepers arguing about cricket, past the clerk who was having to go and work abroad (‘I love Pakistan but Pakistan doesn’t love me back and is forcing me to leave!’), past the government-run schools where the teachers taught only the barest minimum so the pupils would be forced to hire them for private tuition, past the girl pasting a new picture into her Aishwarya Rai scrapbook, past the crossroads decorated with giant fibreglass replicas of the mountain under which Pakistan’s nuclear bombs were tested, past the men unworthy of the rights their women conferred on them, past the trucks painted with the colours of jewels, past the six-year-olds selling Made in China prayer mats at traffic lights, past the ten-year-olds working in steel foundries, past the poet who was a voice in everyone’s head telling them what they already knew, past the narrow alleys of the bazaars where it was possible to get caught in human traffic jams and stand immobile for half an hour, past the fields of sorghum and sugar cane and pearl millet, past the most beautiful, surpassingly generous and honest people under the sky, past the mausoleum of a saint who arrived on a visit and was murdered because the people knew his grave would bring pilgrims and trade to their village, past the men and women for whom it was impossible to believe that there was no God and that He wasn’t looking after them, because how else could they have been spared the poverty, destruction and random violence that lay all around them?

Getting off the train he rode to the Indus on the motorbike and on towards the mansion. Why had he gone so far away from here? Because he had to take Wamaq’s body to Lahore, because Wamaq had always said he would be buried in the same cemetery as his namesake poet. Walking away from his brother’s grave, his mind had stumbled into the void from which it was only now emerging.

It was fully dark by the time he climbed the mansion’s boundary wall and entered the room at the back. As he crossed it he felt the presence of the animals and birds in the darkness around him, the stags with antlers weighing a third of their bodies, the glittering Gilgit butterflies under their glass dome, the cheetah whose spots made it look as though it had come in out of a black rain. Silent, he stopped in front of the door.

She undid the latch on the other side and blindly reached out her hand to take his, the absence of light so complete around them that their strongest glances were absorbed and utterly disappeared. He led her to where he knew there was a divan covered in a dust sheet.

They undressed and in the glow of the gold attached to her skin they saw each other for the first time since becoming separated all those years ago. Gently they touched each other, he mindful of her torn back, she kissing his mouth and throat and chest, the parts of his body he used for singing. No one – not even they themselves – knew the origins of their attachment. Perhaps the earliest incident had been the mullah beating Qes for not having memorized his Quranic lessons, and bruises appearing on Leila’s body.

As they picked up their clothes afterwards, he noticed the small rips and tears in various locations on her garments. But she was smiling with happiness just to be near him. Dressed, they were once again in the darkness.

‘I need something from my room before I go.’

‘All right.’ There was no fear or hesitation in the voice. They stepped into the corridor and with complete self-possession walked towards her room, entering a hall and going up a flight of stairs. He saw her wooden bed with the many nails driven into it, making outlines of her body. She went to the picture above the bed. Throwing aside the knife she took from behind it, she opened the frame and removed the picture. On its back she had written down the secret names that she had given to her four missing daughters.

They were descending the stairs when they saw Timur in the large hall. They stopped.

He was looking at one of the doors that opened on to the hall – it led to the suite of rooms occupied by the new wife. They watched as a devastated Razia opened the door and fell into his arms. ‘It’s not a boy,’ she said, weeping. In her right hand was the ancient dagger with which the umbilical cords were always cut.

Timur separated himself from his mother and stood looking at the floor in a dazed state. Picking up the table that held a vase of plastic lilies, he hurled it against the wall with an immense roar. Leila moved backwards on to a higher step but Qes remained where he was. Razia was weeping, her eyes shut.

As the moments passed and they waited for Timur to look up and discover them, Leila came back down and stood beside Qes.

At that moment, a dozen of Timur’s men entered the hall, all of them armed.

‘What do you want?’ Timur turned to them and bellowed.

One of them came forward and prepared to speak up. He was wearing black clothes and only when red spots materialized on the floor below him did it become obvious that he was bleeding. ‘Nadir Shah is on the island. He has complete control.’

‘Why is Allah punishing us good Muslims?’ Razia exclaimed.

‘That fucking island!’ Timur shouted. ‘Set fire to it – the building and everything in it, the trees and every last blade of grass. Burn even the water around it!’

The old woman let out a cry of horror. ‘What are you saying, Timur?’

The man in black said, ‘We can’t get near it. They have rocket-propelled grenades and there are landmines all along the edge of the island. We don’t know where they got them from. He and his sons must have developed links with the jihadis.’

‘I don’t care. Take every bandit and son of a whore in this house and go and burn it all to the ground.’

Razia grabbed his arm. ‘You can drive him off another way. Allah is on our side, remember.’

‘Where is your Allah and how many cannons does he have?’ Timur said. ‘Stay out of it, it doesn’t concern you.’ Then he turned squarely to her. ‘And it’s your fault that I am alone against him and his sons – why didn’t you perform your duty as a woman and give me brothers?’

Razia raised the hand with the dagger to her mouth and bit her knuckles, the long dazzling blade with the verses of the Quran etched on to it jutting from her fist. She stepped away from him, the eyes ringed with white lashes wide with surprise, the head lowered as she seemed to recover and, with a fixed empty smile, said, ‘The fate of the mosque does concern me. It concerns me as a Muslim. Angels sent by Allah Himself built that mosque …’

Leila tightened her grip on Qes as Timur struck the old woman hard on the face, knocking her to the ground, the elegant dagger rattling to the other end of the hall. ‘I am sick of all this,’ Timur said and he bent down and grabbed hold of the thousand-bead rosary and tore it to pieces, sending the little black spheres flying in all directions. Some of them even slipped under the door to the new wife’s rooms. He straightened and turned to his men.

‘What a

re you still doing here? Didn’t you hear my orders?’

‘Call them back, in the name of Allah,’ Razia pleaded as she wept on the floor.

He stood above her with his loud breathing and then walked over to the dagger. He picked it up, went to the door behind which the birth had just taken place and kicked it open with his foot. Screams and cries went up in the room, the sounds of panic. Leila attempted to stop Qes but he stayed her gently and went down the staircase at great speed, she following a few steps behind.

‘For the last time, don’t do that to the mosque,’ Razia was saying wretchedly, scrabbling around for her rosary beads with her fingers, as Qes and Leila went past her. They heard Timur give a great enraged shout and then an immense silence descended on the world.

Leila and Qes entered the room and saw that the new mother, with her hands red and an expression of crazed hatred on her face, was standing above Timur, who lay on the floor, his mouth still open from that shout. The woman stepped back as he pulled the dagger out of his breast and, the instinct for force still undamaged within the confused and dying mind, stabbed his own stomach with it, once, twice, driving the blade most of the way in each time as the blood welled out of his mouth through gritted teeth. He plunged it blindly into his thigh and groin, and into his face below the right eye, and lastly into the house itself, stabbing the granite floor beside him. Against the walls stood the motionless servant girls, and the midwife clutching the minutes-old human being. She came forward and handed the baby to its mother.

Timur’s blood roamed the floor. Razia, having finally gathered the remains of her rosary from the hall, entered and slowly began to pick the beads off the bedroom floor, each new one bringing her deeper into the room, and closer to Timur’s body. Many of them she collected out of his blood. One lay near his hand – the hand that held the dagger embedded up to the hilt in the stone floor. Only then did she seem to see him.

B005OWFTDW EBOK

B005OWFTDW EBOK