- Home

- Freeman, John

B005OWFTDW EBOK Page 7

B005OWFTDW EBOK Read online

Page 7

Jinnah, for all his secular habits, is partly to blame for this posthumous transformation. He often said one thing, but did another. He carved out his state on the basis of Islam and rallied the support of the Islamic religious leaders, but never intended that Pakistan would be a theocratic state. When he was garnering the support of the imams, photographs show Jinnah looking remarkably uncomfortable. In one shot he stands under a banner written in Urdu – ‘Allah is Great’ – looking terrified of the throngs of youth jostling around him.

The Jinnah portrait in the inner sanctum at the army headquarters in Rawalpindi – the room where Pakistan’s top commanders meet each month around a long, oval, polished wood table – presumably reflects the Pakistani Army’s verdict on Jinnah. A tall, lean, elegantly dressed Jinnah, in beige summer suit, white shirt and tie, sits in a 1940s art deco armchair, his right arm draped over the back of the chair, a cigarette in his fingers. He could be mistaken for an imperious, pre-World War II Hollywood producer. Outwardly, there is an eerie echo of the current army chief, the most powerful man in Pakistan, General Parvez Ashfaq Kiyani, in military fatigues, erect and handsome, who presides at the table in front of the Jinnah portrait chain-smoking cigarettes much as the founder did.

There seems little question that Jinnah would be shocked by Pakistan today. His daughter, Dina Wadia, now in her nineties and living in Manhattan, has told acquaintances that her father must be turning in his grave. On 11 September 2001, exactly fifty-three years to the day after his death, al-Qaeda showed the world how far Islamic extremists had eaten into the fabric of Pakistan.

A civilian government tarnished by the corruption and nepotism that Jinnah warned about in his inauguration-day speech is nominally in charge. But the army essentially runs the show. In July, the government granted General Kiyani an unprecedented three-year extension of his term, handing the military even more power. The military receives about 17 per cent of the total state budgetary expenditure, a precedent that Jinnah established when he devoted an overwhelming proportion of Pakistan’s first budget to the army.

Today, the Pakistani Army is convinced that the India Jinnah left behind is the ultimate enemy. To offset what it sees as India’s far greater economic and military strength, Pakistan uses Islamic militant groups to fight against Indian interests in Afghanistan and, on occasion, within India. Other militant groups have turned against Pakistan itself, and in the last year the army has fought against them. But the strategy of supporting some Islamic groups, and fighting others, further erodes the chance for secularism to have a dominant role in modern Pakistan. The Jihadistan that looms on the horizon as the future Pakistan, a likely compromise between extremist groups and the army, would not have a place for Jinnah today, regardless of how he portrayed himself.

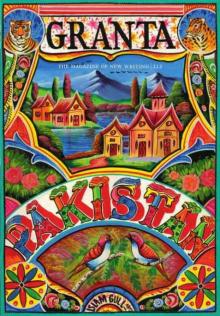

GRANTA

KASHMIR’S FOREVER WAR

Basharat Peer

On an early December morning in 2009, I was on a flight home to Kashmir. It doesn’t matter how many times I come back, the frequency of arrival never diminishes the joy of homecoming – even when home is the beautiful, troubled, war-torn city of Srinagar. Frozen crusts of snow on mountain peaks brought the first intimation of the valley. Silhouettes of village houses and barren walnut trees appeared amid a sea of fog. On the chilly tarmac, my breath formed rings of smoke.

The sense of siege outside the airport was familiar. Olive-green military trucks with machine guns on their turrets, barbed wire circling the bunkers and check posts. Solemn-faced soldiers in overcoats patrolled with assault rifles at the ready, subdued by the bitter chill of Kashmiri winter. The streets were quiet, the naked rain-washed brick houses lining them seemed shrunken. Men and women walked quietly on the pavements, their pale faces reddened by the cold draughts.

In Kashmir, winter is a season of reflection, a time of reprieve. The guns fall silent and for a while one can forget the long war that has been raging since 1990. In the fragile peace that nature had imposed, I slipped into a routine of household chores: buying a new gas heater for Grandfather; picking up a suit from Father’s tailor; lazy lunches of a lamb ribcage delicacy with reporter friends; teaching young cousins to make home videos on my computer. Yet I opened the morning papers with a sense of dread, a fear of seeing a headline printed in red, the colour in which they prefer to announce yet another death – the continuing cost of our troubled recent history.

Political discontent has simmered in the Indian-controlled sector of Kashmir since partition in 1947, when Hari Singh, the Hindu maharaja of the Muslim-majority state, joined India after a raid by tribals from Pakistan. The agreement of accession that Singh signed with India in October 1947 gave Kashmir much autonomy; India controlled only defence, foreign affairs and telecommunications. But, in later years, India began to erode Kashmir’s autonomy by imprisoning popularly elected leaders and appointing quiescent puppet administrators who helped extend Indian jurisdiction. India and Pakistan have fought three wars over Kashmir since then. In 1987, the government in Indian-controlled Kashmir rigged a local election, after which Kashmiris lost the little faith they had in India and began a secessionist armed uprising with support from Pakistan. The Indian military presence rose to half a million and by the mid-nineties Islamist militants from Pakistan began to dominate the rebellion. The costs of war have been high: around 70,000 people have been killed since 1990; another 10,000 have gone missing after being arrested. Although there has been a decline in violence in the past few years and the number of active militants has reduced to around five hundred, more than half a million Indian troops remain in Kashmir, making it the most militarized place in the world. India and Pakistan have come dangerously close to war several times – once after the terrorist attacks on the Indian Parliament in 2001, and more recently after the attacks on Mumbai in November 2008.

And the attacks continue. A few weeks after I left Kashmir again, on the cold afternoon of 7 January, two young men walked through a crowd of shoppers in the Lal Chowk area in Srinagar. They passed bookshops, garment stores, hotels, and walked towards the Palladium Cinema, which once screened Bollywood movies and Hollywood hits such as Saturday Night Fever, and was now, like most theatres in Kashmir, occupied by Indian troops. As they neared the Palladium, the two men took out the Kalashnikovs they had been hiding and fired several shots in the air. One threw a grenade at a paramilitary bunker. Passers-by rushed into shops for safety; shopkeepers downed the shutters. Hundreds of armed policemen and soldiers drove from the military and police camps nearby, surrounded the hotel and began firing. The hotel caught fire.

The fighting continued for twenty-seven hours before the two militants were killed. The police announced that the militants were from the Pakistan-based terrorist group Lashkar-e-Taiba (the Army of the Pure), which had also been responsible for the November 2008 attacks on Mumbai. One of them was from Pakistan. Although most of the Kashmiri guerrillas who had started the war are either dead or have laid down their arms, the second militant, Manzoor Bhat, was a twenty-year-old from a village near the northern Kashmir town of Sopore. I was curious about what had led Bhat to join one of the most dangerous Islamist militant groups, many of whose members are from Pakistan.

I left my parents’ house on a calm May morning of no news and began driving out of the city to Bhat’s home. The village of Seer Jagir is a palette of apple trees and rice paddies, brown wood and brick houses. Old men smoked hookahs and chatted by shop fronts in the village market. Schoolboys in white-and-grey uniforms waited for the local bus. Everyone knew where Manzoor, the martyr, lived. On the outskirts of the village an old man and a boy sat by a cowshed. The sombre-faced boy in a blue pheran was Bhat’s brother. He led me past the cowshed to an austere, double-storeyed house. His mother, Hafiza, a wiry woman in her late forties, joined us a few minutes later. She wore a floral suit and a loosely tied headscarf. ‘I was feeding the cows,’ she said in apology. Hafiza and her husband, Rasul Bhat, had three sons: an older one who worked in a car garage; the youngest son, the student who sat wit

h us; and Manzoor, the dead militant. Though the Bhats lived amid a great expanse of fertile fields and orchards, they owned only a small patch of land, which produced barely enough rice to feed the family. Bhat gave up his studies after ninth grade and began work as an apprentice to a house painter. He learned fast and had in the past few years painted most of the houses in the neighbouring villages. ‘He made around 8-9,000 rupees (US$200) a month,’ Hafiza told me. ‘He bought the spices, the rice, the oil, the soap. He ran the house.’ She fell silent, her eyes fixed on a framed picture of Manzoor: a round, ruddy face, shiny black eyes and a trimmed beard. I was struck by the younger brother muttering something, repeating his words like a chant. ‘He bought me clothes and shoes. He bought me clothes and shoes.’

On 1 September 2008, Bhat left home in the morning, ostensibly for work. He stopped in the courtyard and greeted his mother as usual. It was the first day of Ramadan. He didn’t return in the evening. Hafiza and Rasul assumed their son had stayed with a friend. They got another friend of his to call the phone Bhat had recently purchased; it was switched off. They tried again the next morning; the phone was still off. ‘We feared he might have been arrested by the military,’ Hafiza said. Rasul went to a police station and filed a report about his missing son. Then he went to several military and paramilitary camps in the area, seeking information. A police officer told him that his son had joined the militants.

And here we have a familiar story. Two weeks before Bhat signed up, he had joined a pro-freedom march from the nearby town of Sopore towards the militarized Line of Control, the de facto border. The protests were provoked by a land dispute with the government and quickly morphed into a call for independence.

On 11 August, Bhat and his fellow protesters marched on the Jhelum Valley road which had connected Kashmir with the cities of Rawalpindi and Lahore prior to partition, before the Line of Control stopped all movement of people and goods between the two parts of Kashmir. When the protesters – riding on buses, trucks and tractors – reached the village of Chahal, fifteen miles from the Line of Control, Indian troops opened fire. Bhat saw unarmed fellow protesters being hit by bullets and falling on the mountainous road. Four were killed at Chahal, including a sixty-year-old separatist leader, Sheikh Abdul Aziz. In the months that followed, the scene in Chahal was repeated as hundreds of thousands of Kashmiris responded, marching in peaceful protests. They were often met with gunfire. By early September 2008, an estimated sixty protesters had been killed, and up to six hundred reported bullet injuries. Kashmir was silent and seething, crouching like a wildcat. Indian paramilitaries and police were everywhere, armed with automatic rifles and tear-gas guns.

Many of the injured from across Kashmir had been brought to the SMHS Hospital in central Srinagar. The hospital complex is surrounded by pharmacies and old buildings with rusted tin roofs. The surgical casualty ward has a strong phenyl smell, the cries of the sick and the wails of relatives echoing against its concrete walls. Here I met Dr Arshad Bhat (no relation to Manzoor), a thin, lanky man in his late twenties. The night before Manzoor Bhat, the would-be militant, saw protesters being shot near the Line of Control, Dr Bhat slept uneasily on a tiny hospital bed in the doctors’ room. The next morning he walked into the surgical emergency room with five other surgeons at nine thirty. He and his colleagues were expecting an influx of wounded protesters. Within two hours, streams of them, hit by police fire, were pouring in. He summoned every team of surgeons in the hospital; some thirty doctors arrived and by the end of the day they had treated a few hundred people with grave bullet wounds. ‘We might have saved more,’ he told me, his voice full of regret, ‘if they had not tear-gassed the operating theatre.’

Several young men I interviewed pointed to the killings during the protests of 1990 to explain their decision to join militant groups. Yasin Malik, then a wiry twenty-year-old from Srinagar, worked for the opposition during the rigged 1987 election campaign. After the election, many opposition activists, including Malik, were jailed and tortured. Malik and his friends decided to take up arms against Indian rule and cross over to Pakistan for training after their release. By the winter of 1990, Malik was leading the Jammu and Kashmir Liberation Front (JKLF), a guerrilla group that became the focus of overwhelming popular support.

‘Self-determination is our birthright!’ – all of Kashmir was on the streets shouting it. In those heady days, an independent Kashmir seemed eminently possible. But India deployed several hundred thousand troops to crush the rebellion; military and paramilitary camps and torture chambers sprang up across the region. Indian soldiers opened fire on pro-independence protesters so frequently that the latter lost count of the casualties. Before long, thousands of young Kashmiris were crossing into Pakistan-administered Kashmir for arms training, returning as militants carrying Kalashnikovs and rocket launchers supplied by Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence Agency (ISI). Assassinations of pro-India Muslim politicians and prominent figures from the small pro-India Hindu minority followed, leading to the exodus of over a hundred thousand Hindus to India.

Pakistan was wary of the JKLF’s popularity, its demand for an independent Kashmir, and chose to support several pro-Pakistan militant groups who attacked and killed Malik’s men. Indian troops killed many more. Malik spent a few years in prison in the early nineties; his body still carries the torture marks as reminders. In prison, he read works by Gandhi and Mandela. On his release in 1994, he abandoned violent politics, turned the JKLF into a peaceful political organization and joined a separatist coalition called the Hurriyat (Freedom) Conference, which pushed for a negotiated settlement of the Kashmir dispute.

By the time Malik came out of prison, however, a pro-Pakistan militant group called Hizbul Mujahideen dominated the fight against India. Its leader was Syed Salahuddin, a Kashmiri politician turned militant who had been a candidate for Kashmir’s assembly in the 1987 elections. By the late nineties, most of Hizbul Mujahideen’s Kashmiri fighters had either been killed in battles with Indian forces or arrested, or had spent time in Indian prisons and returned to civilian life, like Malik’s men. Pakistan’s ISI began backing jihadi groups like Lashkar-e-Taiba, which had no roots in Kashmir politics and were motivated by the idea of a pan-Islamist jihad. Hafiz Muhammad Saeed, a Lahore-based former university professor and veteran of the Afghan jihad, heads the Lashkar-e-Taiba. Most of Saeed’s recruits came from the poverty-stricken areas of Pakistan’s Punjab province. The jihadis from Pakistan introduced suicide bombings and took the war to major Indian cities – most dramatically with their attack on the Indian parliament in 2001, which brought India and Pakistan to the brink of full-scale confrontation.

Yet by late 2003, after vigorous American and British diplomatic intervention, a peace process between India and Pakistan was under way. The insurgency began to wane. Pakistan reduced its support to insurgent groups and India’s long campaign of counter-insurgency appeared to be a success. However, Kashmir remains heavily militarized, and the abuse of civilians by Indian security forces continues, fuelling more rage and attracting recruits for Islamist radicals like Saeed.

The dead speak in Kashmir, often more forcefully than the living. Khurram Parvez, a thirty-two-year-old activist, is part of a Srinagar-based human rights advocacy group, the Jammu and Kashmir Coalition of Civil Society ( JKCCS), which produced a report in 2009 exposing hundreds of unidentified graves in the Kashmiri countryside. We met in a garden café in Srinagar. Parvez, a tall, robust man with intense black eyes, walks with a slight limp. In the autumn of 2002, he was monitoring local elections in a village near the Line of Control. As he drove out of the village with a convoy of military trucks ahead of him, a group of militants hiding nearby detonated an improvised explosive device which blew up under his car. The driver and his friend and colleague, a young woman, Aasiya Jeelani, died in the attack. Parvez lost his right leg. Several months later, with the help of a German-made prosthetic, he began to walk again and returned to work. ‘I couldn’t give up,’ he said so

ftly. His engagement with the pursuit of justice in Kashmir has been personal from the beginning. His grandfather, a sixty-four-year-old trader, was one of the protesters killed by the Indian paramilitaries on the Gawkadal Bridge in January 1990. For months, Parvez had thought of taking up arms in revenge, but was persuaded to stay in school by his family. They lived on Gupkar Road, where the Indian security forces ran some of the most notorious detention and torture centres in Kashmir. Almost every other day, he saw desperate parents walking to the gates of the detention centres in his neighbourhood, looking for their missing sons.

Parvez’s cousin and mentor, the lawyer Parvez Imroz, co-founded the Association of Parents of Disappeared Persons, along with a Srinagar housewife Parveena Ahangar, whose son, Javed, had been missing since early 1990, when he was seventeen, after being taken from their home in a night raid by the Indian Army. Ahangar and Imroz campaigned for information about the whereabouts of 10,000 people who had disappeared in Kashmir after being taken into custody by Indian troops and police. Parvez joined them full-time after graduating from college; by late 2005, when a devastating earthquake struck Kashmir’s border areas, he was a veteran of civil rights activism. ‘We were doing relief work in the earthquake-hit areas when we began hearing about mass graves of unidentified people,’ he told me. His group placed several advertisements in Kashmiri papers requesting that people contact them with any information they had about the unidentified graves. Parvez, Imroz and a few other activists travelled widely, documenting this information. Their report, ‘Buried Evidence’, startled Kashmir.

B005OWFTDW EBOK

B005OWFTDW EBOK